by Rachel Hoyle

As a twenty-something not too far removed from my college years, I still find myself surprised at the lengths to which classmates would go to acquire and ingest any kind of alcoholic beverages for as little money as possible. From the “two-buck-chuck” wines at Trader Joe’s that my classmates would promise weren’t as bad as they sounded, to the sale bins of various liquors at our local liquor store, let’s just say that my palate for spirits has improved tremendously since graduating

Stumbling upon Caroline Eustis’ fruit wine recipes, as recorded in her and Governor Eustis’ European Diary (1814-1818) has given me an additional level of appreciation for the better sort of bottled and pre-prepared drinks we can find in our local supermarkets or liquor stores. Madam Eustis recorded recipes for both gooseberry and orange “wine” – and each would take roughly six months to mix and ferment through various stages of their production. While this seems like a long process, it is relatively hands-off once the mix is made. Most of the time is spent letting the drinks ferment in barrels or casks.

The basics of each recipe for a fruit or flower wine involve the same process: “to boil the ingredients, and ferment with yeast… Some, however, mix the juice, or juice and fruit, with sugar and water unboiled, and leave the ingredients to ferment spontaneously.” For both gooseberry and orange wine, the reader will mix the fruit with water and sugar, let ferment naturally for six to twelve months, then bottle. Helen Wright outlined in her 1909 collection Old-Time Recipes for Home Made Wines, Cordials, and Liqueurs that there are an astounding number of recipes to be found in historical collections from the nineteenth century. Anything from fruit, to herbs, to the bark of trees, to honey, molasses, or even flowers was used to make drinks. Among my personal favorites are tomato wine, rose cordial, and molasses beer.

Curiously it is nearly impossible to make a Google search for orange wines today. While Madam Eustis knew orange wine as a liqueur-like drink made from fresh oranges, the recent trend of “orange wine” is named thus for its amber color. It is made by leaving the skins on white grapes while they ferment, resulting in a white wine made in a similar way to red wine. According to the Encyclopedia Britannica (the most official source I could find on this topic), wine is exclusively made from grapes, and not the other fruits, herbs, or flowers that nineteenth-century households would use for their “wines.” Therefore, “wine” serves as an appropriate colloquial name for the drinks Madam Eustis and other women knew how to make but may not be the most accurate term for them. Just don’t tell any sommeliers.

I have no doubt that Madame Eustis, as a politician’s wife tasked with entertaining Massachusetts’ political and social elites, crafted a far better concoction than anything I found in the $5 bin at my college’s liquor store. Eventually, I hope to replicate her fruit wine recipes myself – when I do, I will certainly provide an update here. But given how long they take to ferment, don’t hold your breath.

A diagram of the basement of the Shirley-Eustis House during the time Governor and Mrs. Eustis lived there. The wine cellar is highlighted in yellow. Perhaps Mrs. Eustis fermented the very oranges that she grew in her greenhouse in that cellar.

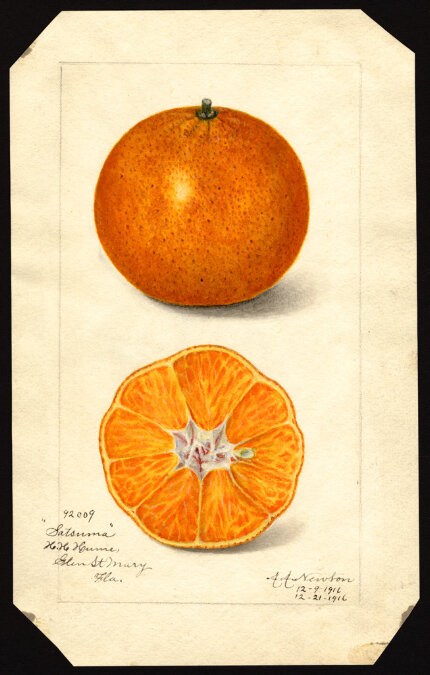

Above: A 1916 drawing by botanical artist Amanda Altamira Newton of Citrus sinensis, also known then as the “China orange”, oneo the only two species widely available in the New World during the Eustis’s time. The other was the Seville orange, Citrus aurantium.