1747 TO THE PRESENT

A History Blog for the Shirley-Eustis House Association.

The Erskine Family in the Shirley Place Tenements, Pt. 1

This article was featured in the Summer 2025 Shirley-Eustis House Newsletter

From 1874 until 1913, the Mansion at Shirley Place was subdivided into apartments and rented out. At any given time, there were approximately seven families living in extremely close quarters with one another. These people held a wide range of jobs: a minister, a barber, watchmaker, teamster, painters, nurse, insurance agent, tailors, cooks, and more. Almost all immigrants to the United States, almost all working class, and many just a single paycheck away from abject poverty.

The residents of Shirley Place were representative of the intense changes Roxbury experienced in the nineteenth century. In less than a century, Roxbury went from a pastoral, well-groomed English landscape to a haven for the working class and for the factories that employed them.

One family in particular stands out among the tenement-era residents at 33 Shirley Street. The Erskines lived here for fourteen years, at some points with three generations inhabiting the same space at one time. It is unclear how many apartments the family rented inside Shirley Place, but it seems to have just been one, as only one of the Erskines was listed as “Head of Household” in each year except for 1890. The family grew and changed over time, but at their peak, there were two older adults, four young adults, and two or more small children in the same apartment. If you have been to Shirley Place, imagine six adults and two young children living in a space the size of the Lafayette bedroom – 400 square feet or even smaller.

The “Erskine” name arrived in Massachusetts at Plimoth in the seventeenth century, while the matrilineal line, Curley, had immigrated to Boston in the mid-nineteenth century from Ireland. This mixture of old Pilgrim heritage and new Irish immigration in the Erskine family is an interesting one. Despite nearly 200 years in North America, the Erskines could not claw their way out of poverty by the Victorian era. Records show that they were still moving frequently, their children were still leaving school to begin working at young ages, and they still suffered from the wear and tear of hard labor and factory pollution on the body. The stereotype of Boston in the late 19th century was that Irish immigrants often suffered a cruel life in pursuit of survival – but evidently, so did families who had been among the first European immigrants to Massachusetts.

In 1891, John Erskine, Sr., the family patriarch, died. His wife Margaret followed not long after, and their son William became the head of household in the apartment. William’s sister Elizabeth also moved back into 33 Shirley Street by 1891 with her three daughters, having lost her husband Charles to influenza around the same time she lost her father. In 1892, then, there were a total of five adults, four children, and one newborn infant in the Erskine apartment at 33 Shirley.

While Elizabeth Erskine Stevens’ children accompanied her back to Shirley Street in 1891, her brother Aaron’s children did not stay with their parents: they were all adopted by other families or living elsewhere by 1900. Aaron and his wife Annie had four children, with three surviving until the 1900 census. Each appeared in a different household in that year, but all still acknowledged their Erskine name. Mary, their eldest child, was a boarder in Dover, Massachusetts in 1900. By 1912, she had married and moved to Northampton. John, their eldest son, died of spinal meningitis in 1906. He was working as a mill hand in Dedham. Joseph, the youngest Erskine, was adopted by a farming family in Dedham. Unusually, the adoptive family listed him as “adopted son,” not just “boarder,” on their census record. At the time, Joseph was just 8 years old.

At the start of my research, it was unclear to me why the Erskine children were farmed out in this way. One hint is in Joseph’s birth record: his name appears in the middle of a batch of children born at or taken to the Temporary Home for Women and Children in Boston’s West End. Only his mother, Annie, is listed as a parent on the record, and no home address is given for Annie or Joseph. At first, I wondered whether Annie was living at the shelter for one reason or another when she gave birth to Joseph. Perhaps she wanted him to have a better life than the one the adult Erskines were experiencing in 1892: packed into tenement housing, suffering from diseases, all forced to work to cobble together an income.

However, I learned something different when following the paper trail in the Temporary Home for Women and Children’s records. Their intake rolls, housed today at the Boston Archives, show that Annie was arrested when Joseph was four months old. Joseph, incorrectly listed as “John” in the paperwork, was taken in at the Temporary Home, and evidently adopted not too long after by his future family in Dedham. It is unclear for what Annie was arrested, and it is unclear where Joseph’s father Aaron was at this time.

When Joseph was adopted, child neglect and cruelty was an issue of paramount importance in Boston. Not just among reformers – in the minds of the public, as well. In her work Heroes of Their Own Lives: The Politics and History of Family Violence, Linda Gordon reports that by 1890, 61% of child cruelty and neglect cases were reported to the Boston authorities by family members of the neglected child. While it is unclear exactly why Annie was arrested and Joseph seized by the Temporary Home, it certainly was a pattern for Annie and Aaron Erskine to lose custody of their children for some reason. And early in each child's life, at that.

Tragedy continued to befall the Erskines. Among the family there was a high mortality rate, even for the time, among children and young adults. Of the eight Erskine grandchildren born between 1874 and 1892, just three lived past the age of twenty. Even among the Erskine children born to John, Sr. and Margaret, disease took its toll. Tuberculosis especially ravaged the Erskine family, as it did most families in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In part two of this story, we’ll examine the impact disease had on the Erskines and other poor families in Boston, especially those living in squalid conditions like the tenements at Shirley Place.

Empire of Trees

We’ve been busy

over the past year at Shirley Place removing trees that have grown up where they didn’t belong. One volunteer that won’t be getting the axe anytime soon is this white pine growing in the west lawn. From an aesthetic point of view, it’s not well located. It obscures a fine view of the lawn as you enter Rockford Street. On the other hand, it’s a beautiful, fragrant tree, specifically, an eastern white pine, pinus strobus, a species whose history is linked to that of Governor Shirley. For starters, when the Governor’s contractors built the house in 1747 they used white pine for parts of the frame and interior trims. This was typical. Old growth white pines, oaks, and chestnuts in New England and Canada provided a seemigly inexhaustible supply of building materials for the swelling numbers of colonists invading the New World.

But more importantly for the British Empire, the tall, straight Eastern white pines (sometimes growing as high as 200 feet), provided strong, flexible timbers for His Majesty the King’s naval ships, especially for masts and spars.(the English wryly called mast timbers “sticks”). In North America there were immense forests of white pines stretching for hundreds of miles into the interior. By claiming the biggest trees in these woodlands for the King, the British navy could obtain the lumber cheap. This meant that the navy would not always be forced to buy their timber from Russia via the Baltic Sea. This Baltic trade had never been a good solution for the English. They had to compete with the Dutch and the French in the same market, and of course Russia could demand a premium price for their lumber. At the very least controlling the timber reserves of North America could ensure a back-up supply in the event that it might be closed off entirely during one of the numerous European wars. This new resource also explains why the English had an interest in ousting the French from Canada as they rapidly depleted the New England forests.

Not long after William Shirley arrived in Boston in 1731, he met David Dunbar, Surveyor General of the King’s Woods for the Massachusetts and New Hampshire colonies. Dunbar’s job required him to inventory and mark any white pines within 10 miles of a navigable waterway that had a diameter of 24” or more. The King’s Broad Arrow mark, an arrowhead shape carved into the bark of the tree, signaled that it was the property of the King of England and was reserved for use by the Navy. Colonists were forbidden to cut down for private use any tree so marked.

An empire is easier to color in on a map than to manage on the ground, however, and the King’s own subjects in New England usually disregarded the law. They cut whatever trees they wanted because the mother country would never supply Dunbar with enough men on the ground to enforce it. Dunbar’s job was thus a thankless one. It kept him in continual hot water with Shirley’s predecessor, Governor Belcher, who had long turned a blind eye to the cutting of His Majesty’s trees in order to curry favor with his timber-smuggling colonial supporters. Dunbar and Samuel Waldo, the businessman who had the contract to cut down the King’s masts, also received regular death threats from locals (google the Pine Tree Riot of 1772) on whose property the trees were found.* Belcher filled his letters to England with nasty names for Dunbar, and portrayed him as an instigator. Though a naïve and ambitious Shirley at first tried to wrest the Surveyor’s job from Dunbar, he soon found it to his advantage to ally with Dunbar in opposition to Governor Belcher. With help from his supporters in England, including the energetic Mrs. Shirley, this strategy worked, and Shirley eventually obtained the governor’s office in 1741. Predictably, he too was then hard pressed to navigate a safe political course between the colonial timber barons and the efforts of Dunbar to enforce the claims of the Empire. Shirley’s ability to play both sides accounts for his longevity as Governor— it was nine years before he himself was ousted by the political maneuvering of his enemies. Among them was his old ally, Samuel Waldo. The details of this saga read like and episode of the TV Show Dallas, and it sometimes got as brutal as Game of Thrones. Just substitute trees or “spice” for oil. So our beautiful Pinus Strobus adds its own dramatic chapter to the backstory of Shirley Place, and we’d rather it were in the way than gone entirely.

For an excellent read on the felling of the North American forests in the cause of fortune hunting and empire building, we recommend Annie Proulx’s Barkskins: A Novel published in 2017. Proulx’s story follows two related families across the centuries. One, an Anglo family, grows powerful and rich in the timber trade and the other, a Native American family is broken apart by it.

*When it came time to purchase a tract of Roxbury real estate on which to build his dream house, Waldo supplied him the land.

A beech tree in England marked with the King’s Broad Arrow. Image courtesy of the New Forest National Park Authority's Historic Environment team.

Collections and Connections: Interning at the Shirley-Eustis House

By Rachel Hoyle

Two shoulder yokes from the SEHA collection. For at least 1,000 years yokes like these have been used by peddlers and laborers to carry everything from bricks to water to food and laundry.

I have enjoyed nearly every single aspect of my internship this semester at the Shirley-Eustis House in Roxbury. My duties have led me to a much deeper understanding of how museums operate, from the mundane hanging of Christmas lights for an evening event to the glamorous preparation of the house for use as a backdrop in multiple documentaries. The site’s Executive Director, Suzy Buchanan, has been gracious enough to let me trail behind her on Fridays, learning exactly how she does what she does.

However, when I use the word “nearly,” there is one particular aspect of my internship that has brought about quite a bit of frustration: the lack of original sources to catalog for my budding exhibit. Given that my exhibit will focus on enslaved Africans at the house, some of whom do not even have their names written in the historical record, it is not exactly surprising that no artifacts of their existence have survived the past three hundred years. Add to that injustice the constantly changing structure and use of the Shirley-Eustis House (at one point it was even used as a “home for wayward girls”), and it is a recipe for the reproduction rather than the display of original artifacts.

There are other historians who have made substantive arguments out of fewer artifacts. Robin Fleming, a professor at Boston College, won the MacArthur Genius Grant in 2013 for her work illuminating the lives of lower-class Roman Britons.[1] While artifacts demonstrating how the wealthy lived in Roman-occupied Britain are relatively common, Fleming provided a view of poor and illiterate members of that society that had never been achieved before her landmark work. I relate to Professor Fleming’s struggle of having limited material evidence to interpret a specific point in time, but it is not as if I am the first person studying African enslavement to encounter this problem, either. The staff at the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC), when collecting the first artifacts for display in the museum, ventured around the nation to track down relevant objects. Physical artifacts of African American history had often been either lost, passed around to various families, or stored in people’s attics for generations.[2]

It was not negligence keeping these items stowed away – it was an instinct of preservation. Many African American familiescertainly knew the value of these (heirlooms..Rex Ellis, Associate Director of Curatorial Affairs at the NMAAHC, recalled the moment he first came face to face with infamous slave revolt leader Nat Turner’s Bible. The woman who had decided to gift it to the NMAAHC from its longtime place in her family’s home in Virginia remarked that “It was time for it to leave here…because there’s so much blood on it.”[3] It was not until the NMAAHC’s founding that many of these artifacts were seen outside the confines of a single family or community, because there were few museums and historic sites willing or able to display them with a proper view toward the artifacts’ troubled? and sometimes disturbing histories.

NMAAHC Founding Director Lonnie Bunch began a groundbreaking campaign to collect these artifacts upon learning that the museum had been green-lit. Titled “Saving African American Treasures,” Bunch deployed conservationists proper term is “conservators” and other museum professionals around the United States in an effort to save artifacts which African-American families had protected and preserved for generations. In total, the campaign unearthed tens of thousands of artifacts for the NMAAHC, most of which were free-will donations made by people who decided their personal collections were finally able to be seen and respected in the manner they necessitated.[4] This distinction between a lack of material culture and a preservation of the very same culture is essential. How many other artifacts are still hidden in an attics, trunks, or basements because museums and historic sites have not been ready to display them with respect? How many of those relate to the experiences of enslaved Africans? (A passage from Exodus in Nat Turner’s Bible pictured above left.)

I thought frequently about these stories while I debated my path forward regarding artifacts in my proposed exhibit. Unfortunately, I did not have the time or resources that Bunch and the NMAAHC had to track down material culture relating directly to the house or its enslaved occupants. And while there are surviving manuscripts and records of enslaved Africans in the Shirley-Eustis House, those grainy black and white copies do not have the same effect in an exhibit as tangible, touchable, evocative objects. Even neighborhood oral histories, which provide us an engaging idea of how the house’s story has evolved over time, do not always capture a viewer in the way that material culture does.

It was then that Suzy Buchanan, the house’s Executive Director, offhandedly mentioned something that solved my problem in an instant. In fact, she made two remarks. The first was that in the basement of the Shirley-Eustis House, right in front of the public restrooms, sat a large iron washing kettle. While it was not original to the house, she qualified, it may at least serve as an illustration of some duties enslaved people may have performed in the eighteenth century. If that was reasonable, she said, I could include it in my exhibit. I could hardly contain my excitement. There was one part of my problem rather expertly solved. It was like inspiration had knocked me over the head, and suddenly I realized that the Shirley-Eustis House also had an unexpectedly large collection of historical tools and gardening equipment in the attic of our carriage house. While we may not have been able to tell the stories of those enslaved at the house directly through artifacts with a documented connection, we could still use items in our collection to interpret their experience. This is one of the first experiences I had as a public historian in realizing the work that goes into keeping a detailed, up to date catalog of material objects at a historic site, as well as the reward that effort can reap.

The second thing Suzy reminded me of was that we at the Shirley-Eustis House were not isolated from other museums. While obviously we would not take credit for objects held at other sites, one of the benefits of designing an online exhibit was the ability to link other sites’ collections into the exhibit itself. The mission of fostering public education on enslavement was more important than simply garnering visitors for my own work. If my articles, exhibits, or interpretations led viewers to another site with more relevant artifacts, then I had done my job well. In some cases, too, repositories such as the Massachusetts Historical Society would allow photos of their objects to be used for a small fee. Using these other materials did not signify a failure on behalf of our own collections or interpretation, and there was no need to take it personally. Good interpretation comes first, and collaboration with other historic sites is not a negative by any means.

The dispersion of artifacts from the Shirley-Eustis House occurred due to war, changing ownership, renovation, and the house’s falling into disrepair in the late 19th century. It may be impossible to know where many of the site’s original eighteenth century artifacts ended up, but that does not render us incapable of interpreting that aspect of the house’s history. Learning how to interpret artifacts as an illustration of the lives of African slaves has been a remarkable experience. I only hope that my exhibit does justice to these individual’s memories, and is able to shed light on the ways they lived and worked in an enlightening and respectful manner.

[1] Fleming, Robin. Britain After Rome: The Fall and Rise, 400-1070. United Kingdom: Penguin, 2011.

[2] https://sah.columbia.edu/content/prizes/tony-horwitz-prize/2021-lonnie-g-bunch-iii

[3] Vinson Cunningham, “Making a Home for Black History,” The New Yorker, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/08/29/analyzing-the-national-museum-of-african-american-history-and-culture.

[4] Vinson Cunningham, “Making a Home for Black History.”

Peter Harrison, Part IV

His Excellency Royal Governor William Shirley knew how crucial Peter Harrison had been to the success of the capture of the fort at Louisbourg in 1745, so he sought to reward him in a number of ways. First, he asked him to design some important buildings for him, including his own country estate in Roxbury. Harrison thought that such an important man as Shirley should have a cut-stone house, which is what he drew for him. Shirley gently suggested that there were then no stone quarries in Massachusetts, and further, he could not afford to import either the stonework or the men who could put the stones together, but he would be happy to have a wooden house. Harrison obliged, with a wooden house in which the planked siding was carved so as to look like stone, an invention attributed to Harrison and known as rusticated wood.

Shirley also encouraged Harrison to propose marriage to Elizabeth Pelham in spite of some opposition from her family, who thought that as one of the wealthiest unmarried women in New England she could do better than a mere architect. They were married on 6 June 1746.

Shirley then asked Harrison to redesign Boston’s Old Statehouse, which had just burned down, and to replace the ancient King’s Chapel with a new building (which was never finished). Shirley was also involved with founding a new capital for Nova Scotia at Halifax, so he had Harrison design Saint Paul’s Church there, and he asked him to design the Nova Scotia Statehouse. For the Statehouse, Harrison designed three versions, small, medium, and large; the large was eventually built in 1813, but the other two were also built, the small as Osgoode Hall in Toronto, and the medium as the courthouse at Saint John, New Brunswick. Governor John Wentworth also asked him to design a statehouse for New Hampshire, but the Legislature refused to pay for it, and the design was eventually used in Toronto.

Above left: the Governor’s Council Chamber in the Old State House which was recently restored to its 18th century appearance. Right: St. Paul’s Church in Halifax, Nova Scotia, said to be the oldest surviving building in Halifax today.

Shirley wrote to all the other British colonies and suggested that they engage Harrison to design any statehouse, courthouse, governor’s mansion, church, or college that they might need, and some of them did, including Williamsburg, Virginia where the Capitol had just burned down. Shirley even got Harrison to design a statehouse for Newfoundland in 1749, but they were in no hurry to build it: it was finally built in 1849, but it burned down only a few years later.

Shirley participated in the peace conference at Aix-les-Bains (Aachen), so he procured a diplomatic passport for Harrison to visit France and Germany to see what their architecture was like. At Besançon, he saw the Church of Sainte Madeleine under construction with its columns grouped in pairs, and he later used the same motif at King’s Chapel. In Berlin, he saw the new opera House at Unter-den-Linden and it influenced the Douglass-Hallam Theatre he designed for Kingston, Jamaica.

The Church of Saint Madeleine in Besançon built in 1746. Harrison was inspired by the double embedded columns flanking the main entrance at the right.

Shirley arranged that Harrison should come to the British Isles to meet top officials. He stopped first in Dublin, where Archbishop Arthur Price asked him to design a new cathedral, three parish churches, twelve schools affiliated with the cathedral, three hospitals, and other buildings. You may not have heard of Arthur Price, but he is the man who gave the Guinness family his top-secret recipe for stout in 1753!

Then Harrison stopped in Liverpool, where they asked him to design their large new Town Hall and three churches. When he reached London, he was introduced to George II, who asked him to design a government building in Dublin and two buildings in his native Germany. Prime Minister Pelham, who was a cousin of Harrison's wife, had him design buildings at both Oxford and Cambridge. The Lord Mayor of London had him design three important buildings (one of which was for the new British Museum, but officials ran out of money and never built it), and the High Sheriff of London had him design his very Palladian country house with a dome. Shirley’s cousin, Admiral Washington Shirley, commissioned a country house, Staunton Harold, and a Wentworth cousin ordered a new front to Wentworth Castle, which Horace Walpole famously described as the most tasteful house design in Britain.

Harrison was also introduced to Richard Chauncey, Chairman of the East India Company, which had benefitted so much from Harrison’s work at Louisbourg. Chauncey made sure that Harrison was engaged to design buildings in Saint Helena, Surat, Bombay, Cuddalore, Madras, Calcutta, Bengkulu (Java), and thirteen “Hongs” for the fifteen trading nations at Canton, China, as well as Christ Church there. Harrison became the first person in the history of the world to design buildings on every known continent, with eventually a total of six hundred buildings worldwide.

A late summer spirit

by Rachel Hoyle

As a twenty-something not too far removed from my college years, I still find myself surprised at the lengths to which classmates would go to acquire and ingest any kind of alcoholic beverages for as little money as possible. From the “two-buck-chuck” wines at Trader Joe’s that my classmates would promise weren’t as bad as they sounded, to the sale bins of various liquors at our local liquor store, let’s just say that my palate for spirits has improved tremendously since graduating

Stumbling upon Caroline Eustis’ fruit wine recipes, as recorded in her and Governor Eustis’ European Diary (1814-1818) has given me an additional level of appreciation for the better sort of bottled and pre-prepared drinks we can find in our local supermarkets or liquor stores. Madam Eustis recorded recipes for both gooseberry and orange “wine” – and each would take roughly six months to mix and ferment through various stages of their production. While this seems like a long process, it is relatively hands-off once the mix is made. Most of the time is spent letting the drinks ferment in barrels or casks.

The basics of each recipe for a fruit or flower wine involve the same process: “to boil the ingredients, and ferment with yeast… Some, however, mix the juice, or juice and fruit, with sugar and water unboiled, and leave the ingredients to ferment spontaneously.” For both gooseberry and orange wine, the reader will mix the fruit with water and sugar, let ferment naturally for six to twelve months, then bottle. Helen Wright outlined in her 1909 collection Old-Time Recipes for Home Made Wines, Cordials, and Liqueurs that there are an astounding number of recipes to be found in historical collections from the nineteenth century. Anything from fruit, to herbs, to the bark of trees, to honey, molasses, or even flowers was used to make drinks. Among my personal favorites are tomato wine, rose cordial, and molasses beer.

Curiously it is nearly impossible to make a Google search for orange wines today. While Madam Eustis knew orange wine as a liqueur-like drink made from fresh oranges, the recent trend of “orange wine” is named thus for its amber color. It is made by leaving the skins on white grapes while they ferment, resulting in a white wine made in a similar way to red wine. According to the Encyclopedia Britannica (the most official source I could find on this topic), wine is exclusively made from grapes, and not the other fruits, herbs, or flowers that nineteenth-century households would use for their “wines.” Therefore, “wine” serves as an appropriate colloquial name for the drinks Madam Eustis and other women knew how to make but may not be the most accurate term for them. Just don’t tell any sommeliers.

I have no doubt that Madame Eustis, as a politician’s wife tasked with entertaining Massachusetts’ political and social elites, crafted a far better concoction than anything I found in the $5 bin at my college’s liquor store. Eventually, I hope to replicate her fruit wine recipes myself – when I do, I will certainly provide an update here. But given how long they take to ferment, don’t hold your breath.

A diagram of the basement of the Shirley-Eustis House during the time Governor and Mrs. Eustis lived there. The wine cellar is highlighted in yellow. Perhaps Mrs. Eustis fermented the very oranges that she grew in her greenhouse in that cellar.

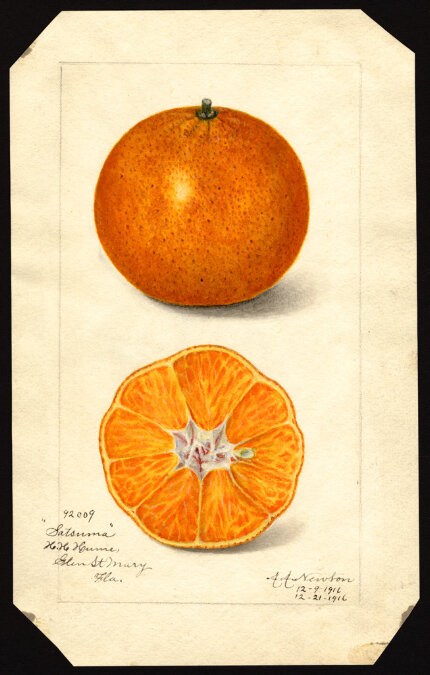

Above: A 1916 drawing by botanical artist Amanda Altamira Newton of Citrus sinensis, also known then as the “China orange”, oneo the only two species widely available in the New World during the Eustis’s time. The other was the Seville orange, Citrus aurantium.

Name that War! Part 3

By Bill Kuttner

Editor’s note: In his December blog entry, Bill Kuttner looked at the impact of 17th century European wars on the process of colonization in North America. In this post, we learn how later European conflicts spilled over into colonial territories, enveloped indigenous populations and seemed only to lead to more warfare.

Dynastic Wars and Colonial Power

While religion did not disappear as an issue, the Peace of Westphalia in 1648 ending the Thirty Years’ War is often considered the close of Europe’s Wars of Religion. But with the new economic doctrine of mercantilism, the race to control resources and markets in foreign lands intensified, leading inevitably to conflict. Not surprisingly, wars continued in Europe, some financed with gold and silver from Mexico and Peru.

These were also the first world-wide conflicts with the mobilization of colonial forces. Issues of world trade and colonial possessions now would need to be addressed, if not necessarily resolved, in the peace negotiations.

While European states might challenge the Ottoman, Aztec, or Mughal Empires whenever the time seemed opportune, conflict between the Christian states in Europe were expected to have some sort of pretext. Any ambiguity in the line of succession in a kingdom, duchy, county, or bishopric might spark military action by one party. Many European powers would choose sides in different combinations as their interests dictated.

In these “Dynastic Wars”, Britain was always on the side opposing the continental superpower, France. Britain’s “balance of power” policy sought to prevent the rise of a continental hegemon and would continue as other continental powers later surpassed France

The boundaries of the contested European territories had been established centuries earlier in the Middle Ages, and once the succession question was settled, most boundaries reverted to the status quo ante. But overseas claims were vaguely defined and in a state of flux. It was still the age of exploration when Spanish missionaries might encounter Russian seal hunters in northern California at the extremities of their imperial dominions. Boundaries might be non-existent, poorly mapped, or ignored, and explorers often did not know where precisely they were.

There were four major dynastic wars significant in American history, and the North American theaters of these wars had their own names. The participants in America also had their own motivations for fighting, and the issues of the North American conflict were addressed in the peace negotiations that ended the dynastic war.

This essay summarizes presents the first three dynastic conflicts and their three associated North American wars. The thesis of this series is that struggles in Europe had important implications for the colonies. By the end of this episode, the colonies are beginning to influence European history. Massachusetts Royal Governor William Shirley emerges as an important figure at the end of this installment and will be joined by young Colonel Washington early in the next.

The pomp and ceremony of European treaty negotiations such as those for the Treaty of Ryswik in 1697, were far removed from the colonies they affected. Months after the treaties were signed and diplomats and their entourages had returned home, colonial subjects received a small pamphlet with the Treaty's terms, which might by then be already out of date.

War of the League of Augsburg, 1689-1697

Charles the II, the unimpressive Elector of the Rhineland-Palatinate died without issue. His brother-in-law, Louis XIV of France, claimed ownership of most of the territories. William of Orange, Stadholder of the Dutch Republic, persuaded Austria, Sweden, Spain, Savoy, and the electors of Bavaria and Saxony to join together to resist Louis. The many new Protestant Huguenot citizens in these lands, recently exiled from France, cheered this move.

In 1689 Parliament invited William of Orange to replace his father-in-law, James II, as King of England. With the addition of British forces, the League acted and after eight years of fighting, Louis gave up his Palatinate claim at the Treaty of Ryswick. France was, however, given Haiti from Spain.

King William’s War

Massachusetts Royal Governor, Sir William Phips, led colonial forces that captured Port Royal, Nova Scotia, today’s Annapolis Royal. A subsequent assault on Quebec failed. The Treaty of Ryswick restored Port Royal to France.

Aside from the Iroquois, most northeastern tribes backed France. Notable massacres included Schenectady and Casco Bay. A former privateer, Phips is best remembered in Massachusetts for ending the Salem witch trials.

War of Spanish Succession, 1701-1714

When King Charles II of Spain died without issue in 1700 Louis XIV claimed the throne for his grandson, crowned as Philip V. Charles agreed in his dying wish. This violated an understanding with Britain and the Dutch Republic that France and Spain would never be united under Bourbon rule.

Again, a dozen European states chose sides. John Churchill, the Duke of Marlborough, led the allies’ largely successful campaigns. Gibraltar [gateway to valuable Mediterranean trading ports] was captured. Philip remained King of Spain, but union with France was forbidden.

Queen Anne’s War

French, Abenaki and Pocumtic fighters from Canada raided Deerfield in 1704. Then Port Royal was captured by New England colonial forces again. The Treaty of Utrech(1713) recognized Britain’s claim to Newfoundland, Hudson’s Bay, and a loosely defined “Acadia,” which included mainland Nova Scotia and the Maine seacoast. Port Royal was renamed Annapolis Royal. France retained Cape Breton Island and (today’s) Prince Edward Island. Soon thereafter construction began on the Louisburg fortress, which would play such a big role in Governor Shirley’s career.

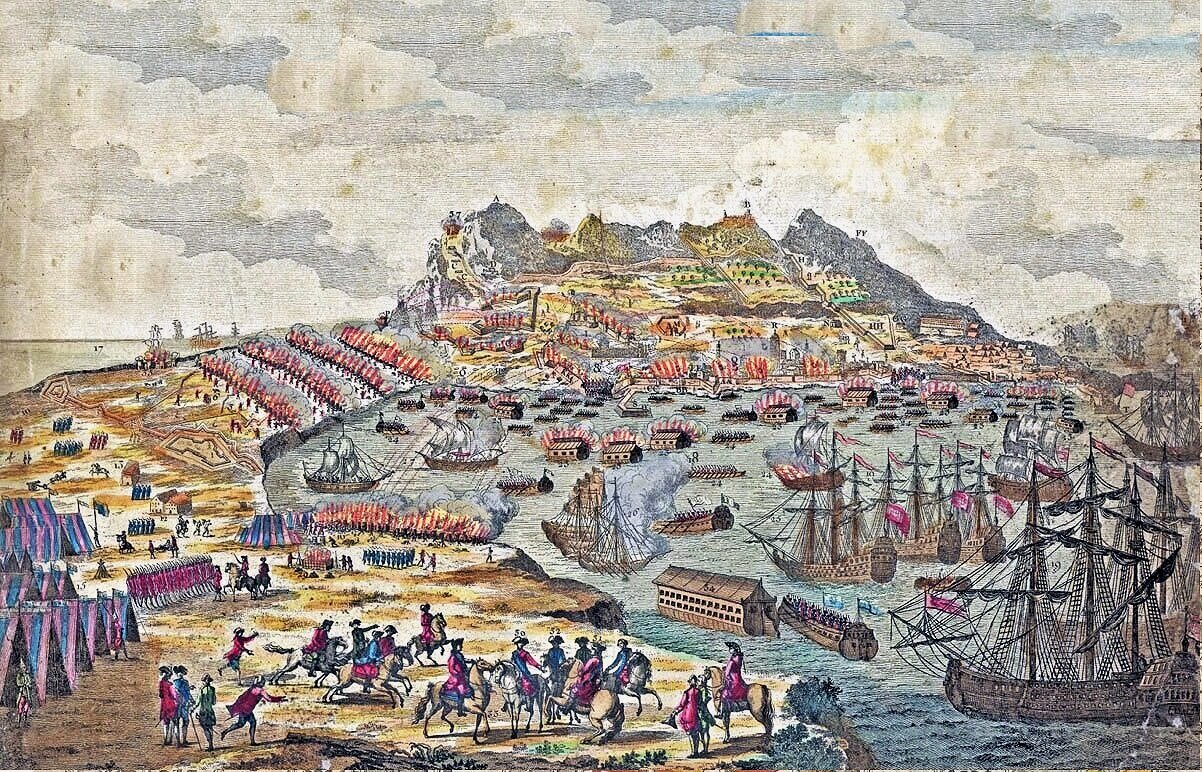

The British Assault on Gibraltar, Spain, a vital control point for the Mediterranean trade routes. British warships bearing their red flags enter the harbor from the right, while lines of troops assault the rock from the left

War of Austrian Succession, 1740-1748

The Holy Roman Emperor, Charles VI, had no male heir. He ruled over many lands with ancient laws. Some allowed rule by a woman; others did not. Charles requested that the European Sovereigns recognize his eldest daughter, Archduchess Maria Theresa, as Queen in lands such as Hungary, and Regent in the other lands for an as yet unborn male heir. Shortly after Charles’ death, the Elector of Bavaria, backed by France, asserted his own claim. European states chose sides.

In a dynastic war-within-a-war, France financed the rising of the Scottish clans under Bonnie Prince Charlie, grandson of the deposed James II, in the Second Jacobite Rebellion. British forces under the Duke of Cumberland, the son of King George II, unsuccessful against the French in Flanders, returned to Britain to face this threat. Cumberland eventually crushed the rebellion at Culloden Moor, infamous for the killing of wounded highlanders.

King George’s War

A notable and unexpected British success was the capture of Louisburg in Nova Scotia by New England forces organized by Massachusetts Royal Governor William Shirley. Negotiating in Aix-la-Chappelle (modern-day Aachen) from a position of weakness, Britain later returned Louisburg to France in exchange for commercially valuable Madras in India. Composer George Frideric Handel celebrated the peace treaty with the Music for the Royal Fireworks (listen here: youtube.com/watch?v=qHTu91hplhE) .

Archduchess Maria Theresa was a formidable figure in the world of absolutist monarchs. She ruled over Austria, Hungary, Croatian, Bohemia, Transylvania, parts of Northern Italy and the Austrian Netherlands from 1740 until 1780. While pursuing reforms in education, medicine, and finance that benefitted her subjects she aggressively quelled religious dissent. All this while giving birth to sixteen children and surviving smallpox.

Marie Antoinette and the “Diplomatic Revolution”

Silesia was a prosperous, German-speaking duchy north of Bohemia, today part of Poland. After the duke died without issue in 1675, Silesia, part of the Holy Roman Empire, came to be ruled directly by the Hapsburg Emperor. The upstart power, neighboring Prussia, asserted that the grounds for Hapsburg rule were faulty.

While not technically allied with France, Prussia took advantage of Austria’s struggle to seize Silesia. Austria tried in the First and Second Silesian Wars, fought in the midst of the War of Austrian Succession, to recover Silesia. With ineffectual support from its British ally, Austrian forces were only able to secure Maria Theresa’s regency, but not Silesia itself.

Maria Theresa’s husband, Francis Stephen, was elected Holy Roman Emperor, and their family quickly expanded including the future emperor Joseph II (portrayed in the movie Amadeus) and his sister, Marie Antoinette. Austria was not ready to give up on its claim to Silesia and sounded out France on the potential of an alliance. France agreed, an event dubbed by contemporaries as the “Diplomatic Revolution.” Fourteen-year-old Marie Antoinette played her obligatory part by marrying the Dauphin of France, the future Louis XVI.

No One is Satisfied

Only the succession issues in Europe seemed to be resolved. Maria Theresa’s regency continued, and Britain’s young House of Hannover survived another Jacobite rebellion. Austria still planned to recover Silesia, and victorious Prussia was for the moment without allies. France did not have a recognized claim to North America’s great river system by which its colonies in Quebec and New Orleans could communicate and support each other. Meanwhile, America’s restless colonists looked to the continent’s interior and saw only opportunity. This is where the spark would ignite what would be the world’s first global conflict.

The British naval assault on Gibraltar, a vital control point for trade around the Mediterranean. The British ships, bearing red flags, bear down on the harbor from the right, while lines of troops make a land assault from the left.

Peter Harrison, Part III: Prisoner!...and some time for toilet tinkering

By John F. Millar

Editor’s note: In our October 2020 installment on Peter Harrison, we traveled with the young architect around the Atlantic perimeter and up the coast of North America to meet his future wife. Still seeking his fortune, he soon headed to French Quebec and the massive French fort at Louisbourg, Nova Scotia. In this chapter, Peter again visits Louisbourg in 1744, but this time as a prisoner of the French. What he acquires there proves invaluable to William Shirley’s efforts to oust the French from the territory on behalf of the British Empire. The battle over what may seem today like a mere outpost, influenced the course of American and European history forever. For more on the context of the conflict surrounding Peter’s capture, see Bill Kuttner’s post “Name that War! Part III”, above.

In June 1744, Harrison was sailing the Boston-owned brig/snow Nancy with a varied cargo from Italy to Boston when he was captured by the privateer schooner Le Succes and brought into Louisbourg as prisoner of war. Since he was already a good friend of Colonel Verrier, he was permitted to be a guest at Verrier’s house rather than confined to a dungeon, provided that he swear that he would not leave the house without permission – they did not want him snooping around the fortifications taking notes.

Verrier felt sorry for him, so he offered him his drafting table and the paper in the drawer underneath. Harrison looked in the paper drawer: Verrier had forgotten that he had left the complete plans of the fortifications in it! Harrison carefully copied down the plans and hid his copies in the lining of his coat; nobody suspected a thing because everyone there was wearing paper in their coats as a good way to stay warm. When Harrison was released on a prisoner exchange a few months later, he took the plans to his friend, Governor Benning Wentworth of New Hampshire, who in turn introduced him to William Shirley.

Caption: The Fort at Louisbourg protected France’s growing fishing and trading activities in Nova Scoti and its busy harbor at Port Royal.

Shirley’s eyes popped out of his head: he had been trying to get the Massachusetts Legislature to sponsor an attack on Louisbourg, and they had repeatedly laughed him out of the room because he had no real soldiers, only farmers and fishermen with guns in their hands. When they saw the Harrison plans, they realized Shirley’s warnings about an imminent French invasion might be correct. They told Shirley to go ahead, so a multi-colony force (men from Massachusetts & its colony Maine, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Connecticut, and New York, and money from New Jersey and Pennsylvania) set sail for Louisbourg on 30 April 1745.

Meanwhile, Harrison had spent time in Newport, courting Elizabeth Pelham, and the colony had asked him to work on the design of the 14-gun brig Tartar which was to be one of the guard-ships for the convoy, and he made the stern look as if it had been designed by the renaissance architect Palladio. While the convoy was approaching Louisbourg, suddenly the powerful 34-gun French frigate La Renomméée appeared out of the fog. Without wasting a second, Captain Daniel Fones steered his tiny brig at the frigate and fired a few broadsides before the frigate could make herself ready to reply. Tartar safely led the frigate far away from the convoy, which the frigate could have completely captured had she not done so.

After the 4,200 Americans had landed near Louisbourg on 11 May, they were supported by a small fleet of British warships under Commodore Peter Warren. Much to everyone’s surprise on both sides of the Atlantic, the powerful fortress of Louisbourg surrendered to the New England amateurs on 28 June 1745. Shirley knew that this action had prevented the French from successfully invading British America. Essentially, we speak English today and we do not all eat croissants for breakfast, thanks to Shirley and Harrison.

Back to Harrison while he was a prisoner: as a ship captain, he was familiar with pumps and valves, and it was not long before he had figured out the details of how to make the world’s first practical flush toilet with the familiar S-shaped exit valve. He enlisted Verrier to provide him with some workmen capable of executing what he had drawn, so Verrier’s Hospital at Louisbourg had a few of the units fitted, which greatly improved sanitary conditions.

Alexander Cummings patent drawing for his flush toilet, presumably based upon Harrison's design. The bowl was flushed by a stream of water flowing dowward through the black tube from a tank suspended above.

After he was freed, he found a letter waiting for him in Newport from authorities in Liverpool, asking him to design a 100-bed hospital. He incorporated no fewer than thirty-six flush toilets in the design, which caused the Infirmary administration to publish the floor-plans, showing each of the toilets! The Infirmary was destroyed in 1824 because it was then too small. Harrison later incorporated flush toilets into many hospitals that he designed, including the 1755 Pennsylvania Hospital at Philadelphia, and the 1758 Stonehouse Royal Naval Hospital near Plymouth, England. Immediately after Harrison’s death, Scotsman Alexander Cumming took out a patent for Harrison’s design.

How Three of Europe’s Major Religious Wars Affected Colonial America

Written by Bill Kuttner

Moravian Church in Winston-Salem, NC

Records of conflict, war, and statecraft date back to hieroglyphics on the walls of pyramids. Indeed, even broad historical accounts that chronicle the advance of human culture still need to keep track of who’s fighting whom where, when, and why. An unfortunate result is that many people view history, with some justification, as a dreary cavalcade of violence. While some people may find it interesting that the Roman legion offered tactical advantages over the Greek phalanx, far more people are inclined to just ignore history altogether.

However, wars did happen and their outcomes influenced to varying degrees the course of history. The beginning of the Protestant Reformation in Europe sets the stage for a series of bloody conflicts which ultimately had surprising influence on American colonial history.

These wars were not just fought over religion, but also over the extent and constraints on royal and imperial power. However, the groupings of armed belligerents fell largely along sectarian lines. Here, in a nutshell, or three nutshells to be precise, is how three of Europe’s major religious wars affected colonial America:

France’s Religious Wars, 1562-1598

Apollos Rivoire tankard. Father of Paul Revere.

This 36-year struggle was actually a series of eight civil wars between French Protestants and Catholics, supplemented by a few extra battles and assassinations. The Saint Bartholomew’s Day Massacre in 1572 launched war number four, and one of the wars was also called the “War of the Three Henrys.”

The French Protestants, called Huguenots, were Calvinists and included many noble and aristocratic families. The upper-class Huguenot cavalry could not defeat the Catholic peasant foot soldiers fielded by the crown.

The dreary struggle finally ended in 1598 with the Edict of Nantes, which offered limited and grudging freedom of worship: nobles could choose Protestant worship, but this was prohibited to lower classes within 20 miles of Paris or in any city with a bishop.

As soon as the ink dried on the Edict of Nantes, however, the crown tried to back out of it. Warfare resumed, and Protestant England tried, without success, to help the Huguenots.

In 1685 Louis XIV simply revoked the Edict of Nantes. This is considered one of the world’s greatest cultural and political miscalculations. Huge swaths of the French middle class simply took their skills and left France, many coming to the British colonies in America. And who should be among them? Silversmith Apollos Rivoire, the father of Paul Revere, came to Boston as part of the Huguenot diaspora.

The English Civil War, 1642-1646

This conflict is usually grouped with the Wars of Religion because the sectarian nature of the opposing forces and the fact that it took place at the same time as the thirty Years War. However, the intractable issues that led to warfare were more political than religious.

To name one of many points of contention, King Charles I wanted more tax revenue, but the power of taxation had for centuries been reserved to Parliament. Charles asserted that Parliament’s powers were over internal revenue, and that the Crown could tax at the water’s edge (meaning levy taxes on imports). To Parliament, this was absurd, and Charles, overplaying his hand, would not seek middle ground.

In 1630 the Puritan minority’s “city on a hill” was going to have to be in the New World. But by 1642 the Puritans held a majority of the seats in Parliament. Parliament had the power to call up the militias and levy taxes to pay them. The King summoned his forces based on feudal obligations. The King’s “cavaliers” easily outmatched the Parliamentary forces.

Meanwhile, Massachusetts Governor, Sir Henry Vane, had been elected in Massachusetts under our first colonial charter. Vane returned to England to fight alongside Puritan Cromwell as the improving Parliamentary army gradually turned the tide against the Royalists.

The religious aspect of this conflict was between the Anglican, “high church” practices insisted upon by the King Charles, and the simpler worship practices of the Puritans. The war was over political issues, but the outcome would shape the nature of English religious life. A century later, appointed Royal Governor William Shirley strongly supported Anglican worship in America—he was instrumental in funding the construction of King’s Chapel in Boston--, but he was cordial and tolerant of the Puritan (then called Congregational) churches, as well as the Presbyterian and Baptist societies popping up in Boston.

This episode offers another telling comparison with the colonial experience. After repealing the Stamp Act, Parliament seemingly concurred that the colonies should be responsible for taxing themselves. However, Parliament asserted that it retained the power to tax at the water’s edge. Facing a colonial boycott, Parliament gave up taxing imports to the colonies, except for the “symbolic” tea tax. The rest is history. But this time it was Parliament making the exact same mistake that Charles made over a hundred years earlier.

The Thirty Years War, 1618-1648

Voltaire quipped that the Holy Roman Empire was “Neither Holy, nor Roman, nor an Empire.” The Hapsburg Emperor in Vienna ruled over a number of lands directly, and sort of presided over the others that were actually ruled by local princes. These local princes had been free to allow Protestant worship since the time of Martin Luther.

By 1604, however, the Emperor had been persuaded by the Papacy to push the Counter reformation within the Hapsburg dominions and throughout the Empire to the greatest extent possible. This included firing Protestants from the Imperial civil service. The response was the Defenestration of Prague in 1618, when some Imperial officials were tossed out of a castle window. (They landed in a snowbank so the injury was to stature only.)

Among those displaced by the persecution of Protestants were the Czech-speaking Moravians. After the war many Moravians left their homes and migrated to Saxony at the invitation of the Duke of Saxony. After a generation or two they were German speakers.

Later the Duke of Saxony sponsored Moravian settlements in the American colonies. Bethlehem, Pennsylvania and Winston-Salem, North Carolina were two of the areas settled by Moravians (“Salem” is short for “Jerusalem.”)

Later still, many Hessian soldiers were captured at the American victory at Saratoga. The Continental Army was in no position to run prison camps, so it just let the poor, homeless Germans go. Many made their way to Pennsylvania, found a Moravian community, settled in and became Americans.

Yet More on Pears, the Fruit of Royalty

Book review by Eileen Woodford

The Book of Pears: The Definitive History and Guide to Over 500 Varieties

By Joan Morgan

With paintings by Elisabeth Dowle

Our pear trees at Shirley Place are tucked into themselves now that winter is upon us. The blossoms, the fruit, and now even the leaves are long past and gone. We know, however dead the pears may look to us, that they have a secret life going on in them. They are dormant – “marked by a suspension of activity” according to the online Merriam Webster dictionary from the Latin dormire "to sleep." However, their dormancy doesn’t mean that we can’t enjoy a feast of pears this winter. We can read about them in Joan Morgan’s visually lush “The Book of Pears.”

I discovered the existence of this book over the summer while researching our August blog post about our pear varieties at Shirley Place. I couldn’t get a copy from the library–no reason to explain why–until August after I had handed my article to our blog editors. I was disappointed but understood given that librarians had a lot to do after the reopening. I finally got an email from the Cambridge Public Library telling me that the book was ready for pick up. When I got there, the librarian handed me one of the most beautiful books I have ever held.

Part horticultural history, part travelogue, part gushing love story, the book is a glorious exploration of the hundreds of cultivars of Pyrus Communis and their origins. The history of the cultivated pear stretches back thousands of years. The ancients revered pears and, starting with the earliest times of horticulture, the fruit became the focus of widespread searches for the sweetest and most aromatic fruits. No armchair historian, Morgan, a pomologist and fruit historian, takes the reader on a road trip to northeast Iran, Syria and Kurdistan Iraq to delve into the origins of the western pear – only to say we really don’t know, but isn’t it fun to try and figure this evolutionary puzzle out. After this, we travel with Morgan through Roman times and the debates about the morality of grafting; Medieval Europe, when the pear becomes the subject of intense correspondences between kings, nobles and monks about their cultivation, storage and use; and Renaissance Italy, where fresh fruit became a triumphant finale to any feasts worth noting, resulting in the introduction of new varieties of pears of improved quality.

But it is when we get to France in the 17th century that the passion for pears explodes. It is a dizzying collision of advances in horticultural science, new husbandry techniques and a runaway food craze among the aristocrats. The result is a proliferation of new cultivars with names as elaborate as the Louis IV’s lace and with descriptions of their taste (buttery,) flesh (melting, pink-tinged) and perfume (musky) that border on the sensual.

Everything about French pears during this time is haute.

As Morgan brings us into the 18th and 19th centuries, she introduces us to market pears. This is where our Shirley Place pears come into the story as Morgan deftly weaves together commercial history and horticultural history as horticulturalists in France, England and North America seek ways to bring pears to rapidly growing urban populations. While storage was always an important part of pear cultivation, larger scale commercial shipping and storage became more important than personal cultivation. Disease resistance, ease of growing and guaranteed outcomes in taste, took over as primary considerations. Enter the Bartlett. It was – and still is – appealing for the great productiveness of its trees, good size and, most importantly, can be picked while still ‘green’ and transported long distances. Most pears, unlike other fruits, ripen off the tree. The 20th century brings us refrigeration and pears from Oregon, California, and with NAFTA, Chile.

I cannot leave The Book of Pears without some comment on the names. They are as diverse as the pears themselves. The Italians go in for strong names: Volpina and Fiorenza. The French seem to name them after their mistresses: Duchesse d’Angoulême – or their saints: Jeanne d’Arc. The British name them after their clergy: Vicar of Winkfield, and the Americans after themselves: Bartlett, Richard Peters. (Enoch Bartlett, the man who pasted his moniker on the Bartlett, had an orchard next door to Shirley Place and advised Madam Eustis in her own horticultural efforts.)

We are just beginning to understand the extensive research that we need to understand the full horticultural history of Shirley Place. Our little orchard of apples, pears and cherry trees is a portal not just into the long history of fruit cultivation, but a part of the significant history of horticultural innovation in fruit propagation in the Boston area during the first half of the 19th century – the history that has led the Bartlett pear to be the single most produced fruit in the United States.

I don’t want to return this book to the library. I love lingering over the color plates – watercolors of different varieties of pears. I find not just solace, but joy and hope in this book. It is about growth and beauty, desire and satiety. It is about what humans will do to achieve perfection in a single bite of fruit.

In the meantime, as the virus continues to rage outside, get this book from your library and sink into a delightful exploration of pears. Of course, a glass of perry along with a slice of buttery pear tart would be a lovely accompaniment to your reading. The feast can continue over the winter.

Hibisicus--A Rose by Many Other Names

by Suzy Buchanan

The hibiscus bushes at Shirley Place bore up surprisingly well in the heat and drought of summer 2020. As late as mid-September you could hear the buzzing of the honeybees, carpenter bees and tiny native bees buzzing about the bushes even before you’d see them. Up close you’d find a veritable cloud of the little creatures dive-bombing the deep pink centers of the flowers. It’s a reminder that pollinators are at work all summer, not just in spring.

Hibiscus is an odd duck in the world of gardening: its delicate, tissue-like blossoms emerge on a bush that is as ungainly and squat as a sack of flour, with leaves growing directly out of the branches like hairs sprouting from spindly legs. But unlike the cultivated English roses in Madam Eustis’s garden, the Rose of Sharon, as the hibiscus is also known, is a hardy, willing shrub that doesn’t require a lot of tender nurturing to give its best performance. It tolerates drought and poor soil and doesn’t mind heavy pruning to make it shapelier. In fact, in China’s Hubei province, where hibiscus is native, farmers used to create fences out of densely planted rows of hibiscus. Their square pruning technique encouraged blossoms. It caught on somewhat in Britain when the plant arrived there in the 1600s, but never seems to have taken hold in the United States. That’s a curious fact given that Americans ditched the official Latin term for the bush, Hibiscus Syriacus in favor of the more descriptive Althea Frutex, which translates as “useful flower” or “useful shrub.” What could be more useful to a farmer than a fence? On the other hand, with stones aplenty in the New England landscape, the fence problem had a ready solution.

The square pruned hibiscus makes an attractive and dense hedge.

Americans focused instead on the hibiscus’ ability to dye fabrics a luxurious purple, and for its usefulness as a medicine. The plant’s many curative qualities were reported on by English physician Frederic Porter in his 1871 botany manual for Christian missionaries working in China. He noted that the dried leaves were a useful astringent and diuretic, while the bark, seeds and root could be used to treat dysentery and eczema. This was useful knowledge in a world where modern medicines couldn’t be dropped in by helicopter.

As with every species in our gardens here at Shirley Place, we ponder whether Madam Eustis cultivated hibiscus herself. Maybe althea frutex was too workaday a species for the lofty pursuits of the burgeoning world of scientific horticulture that she was so avidly involved with. A trip to the Massachusetts Horticultural Society’s archives, when they reopen, may answer some of these questions. In the meantime, we’ll keep exploring the gardens, their plants and their history for the multitude of other insights they offer. For example, like so many other more humble and hardy garden staples, hibiscus is today enjoying a resurgence in popularity among gardeners and food foragers. You can enjoy them candied or boiled in tea, and the young leaves are good in salads. The flowers can also be eaten right off the bush. I tried one. The taste is mild and surprisingly sweet. No wonder the bees were all over it. Having been stung before though, I’ll wait until they’re done before I go in for seconds. And maybe we’re due for a post on pollinators without whom we could not write about hibiscus.

Our thanks to Master Gardener Mary Lou O’Connor, who has kept the heirloom garden at Shirley Place civilized this summer iand taught us more than we ever thought one could know about pollinators.

Part II in the Life of Peter Harrison: Going to Sea and Getting a Girl.

by John Millar

In John Millar’s last installment on the life of architect Peter Harrison, we learned of his early training in England under builder-architectWilliam Etty, and of Etty’s first two lessons to the aspiring young gentleman. In this installment we learn Etty’s third rule of practice before we embark with Peter on his travels of the Atlantic world. A life-changing stop in Rhode Island introduces him to his future wife, the aristocratic Elizabeth Pelham.

The third rule that Harrison’s teacher, William Etty had taught Peter was never to charge for drawing churches or other public buildings, so that private individuals would be so dazzled by them that they would want to commission him to design their houses. A look at the list of buildings he designed up through age twenty shows that the large majority of them were churches and other public buildings https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St_Swithun%27s_Church,_Worcester#/media/File:St_Swithin's_Church_from_the_East_-_geograph.org.uk_-_217959.jpg. At such an early date in his career, this well-intentioned strategy was not yet working. He would have to find a second career just to stay alive.

Therefore, he asked his merchant-ship captain older brother Joseph to give him a crash course on how to be a ship captain, which he did. In the meantime, Peter continued his architectural pursuits. By early 1738, when he was just 21 years old, Harrison had designed the Mansion House/Town Hall at Doncaster, Yorkshire for James Paine to serve as builder and two ranges for Guy’s Hospital, London (all at no charge, of course), and he had learned enough from his brother to venture out on his first voyage. He sailed to Amsterdam, Venice, Gibraltar, South America, the Caribbean, and North America. Early in the voyage, he designed an English merchant’s palazzo on the Grand Canal in Venice, where he also saw that the great Palladio had called for his buildings to be painted yellow-ocher with cream trim, so he began to do the same, Shirley Place was painted that way.

The Mansion House at Doncaster, as depicted in 1829.

At Gibraltar, he designed a number of public buildings: the Great Sephardic Synagogue Sha’ar Hashamayim, Holy Trinity Church, the Royal Naval Hospital, Military Barracks on Town Range, the Exchange/Statehouse, and the Guard House.

In South America, he designed the Governor’s Mansion (now the President’s House), the Zedec ve Shalom Sephardic Synagogue, the Martin Luther Lutheran Church, and the Dutch Reformed Church (first classical dome in non-Iberian America, now destroyed) at Paramaribo, Suriname, and the Dutch Reformed Church at Stabroeuk in the Dutch colony of Demerara (the church is now much altered, and the town is now Georgetown, Guyana).

In the Caribbean, he designed the impressive Statehouse, the Nidhe Israel Sephardic Synagogue, and the Da Costa business building at Bridgetown, Barbados, and in Jamaica, Up-Park Plantation House and the Ellis Plantation House, “Montpelier,” neither of which still stands.

In Georgia, he designed Christ Church, Savannah, the Whitefield Orphanage at Bethesda, the Barracks at Frederica, none of which still stand, and Whitefield College, which was never built. In South Carolina, Drayton Hall Plantation House near Charleston is often described as the most beautiful house in America; he designed some furniture to accompany it, both house and furniture decorated with egg-and-dart moldings. In Charleston, he designed the William Bull Mansion https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Bull_House. In Wilmington, North Carolina, he designed the Market/Statehouse, which no longer stands.

In Virginia, he designed the Lee Plantation House “Stratford Hall.” In Maryland, he drew three plantation houses, the Darnall House “His Lordship’s Kindness,” and the Hill House “Compton Bassett,” as well as the now destroyed Dulaney House, Annapolis.

The Lee family plantation in Virginia, with its slave quarters flank either side of the lawn. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

In Pennsylvania, he designed five country houses: the William Peters House “Belmont” (the only one still standing https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Belmont_Mansion_(Philadelphia) ) Andrew Hamilton’s “Bush Hill,” Joseph Wharton’s “Walnut Grove,” Loxley House, and the Kinsey/Pemberton House, as well as the Whitefield Orphanage at Nazareth, and furniture for the Library Company of Philadelphia, decorated with egg-and-dart moldings.

Finally, he arrived in Boston, where he designed the steeple for Christ Church, “the Old North,” and he talked furniture-maker Job Coit into making a secretary-desk of his design, the first ever block-front piece, now at the Winterthur Museum in Delaware. His output on this one trip exceeds what some architects do in a whole lifetime.

In the next few years, he designed a new steeple for Trinity Church, Newport, Rhode Island, and a folly for the three Pelham sisters, now known as “the Old Stone Mill,” Newport – where he met Elizabeth Pelham whom he would later marry. In Massachusetts, he designed Faneuil Hall, Boston for painter John Smibert to oversee the construction, and the diminutive Holden Chapel, Cambridge.

He stopped at the heavily fortified French city of Louisbourg, Nova Scotia, and solved a major problem faced by the local architect Colonel Etienne Verrier with the unfinished main gate of the city. A grateful Verrier gave him a letter of introduction to officials in Quebec City, Trois Rivieres, and Montreal, and he designed buildings there, including mansions for the military and civilian governors, most of which have been destroyed. His good relationship with Colonel Verrier would turn out to be crucial to the rest of his life, as we will see in future posts.

The Comforts of Toast

Written by Suzy Buchanan

A traditional toasting fork could range from eighteen inches to four feet long, depending on the size of the hearth it was used in. Image courtesy of the Barnes Foundation

As a kid, one of my favorite books was The 101 Dalmatians by Dodie Smith (the book came out in 1956, the first movie version in 1961). I especially loved the chapter in which our heroes, the cold and weary Dalmatian dogs, Pongo and Missis, are invited to rest for a night at the home of a grizzled spaniel. Their ancient host sneaks them into the dark warm parlor of his equally ancient human, Sir Charles, who is seated in an armchair in front of a good fire. Sir Charles is absorbed in the task of toasting thick slabs of bread at the fire and loading them with butter. By turns he makes one for himself, and one for the old spaniel, who then slips slice after slice to the ravenous Pongo and Missus. The old dog is happy to share. At the age of ninety—in dog years—he assures them that he’s too old to eat more than a bite or two. The hot, salty toast revives Pongo and Missis in body and spirit, and after a brief nap, they are fit to resume their journey to Hell Hall in search of their kidnapped pups. Buttered toast becomes a cross-species comfort food for man and beast.

Old Sir Charles used a toasting fork (pictured at the top of this post) to cook the bread, a device that requires complete attention to the task of toasting so as not to result in a charred brick of bread. Fine for Sir Charles, but for a busy cook or housekeeper, the toasting fork required too much tending. A more convenient device was the fireside toaster pictured here, which can be seen in just about every historic house museum you’ll ever visit in New England.

Being common, however, doesn’t diminish its clever and attractive design. The toaster in the Shirley-Eustis House collection is of English design and was probably made anytime between 1775 and 1825. It accommodated two fat slices of bread end to end and could be left by the fire until one side was toasted. A loose bolt in the middle of the rack allowed the entire thing to be rotated around with a gentle push of the toe to brown the other side of the bread. Unlike a modern toaster, it could last a lifetime in dog or human years.

How might the residents of the Shirley-Eustis house have enjoyed their toast? Well, probably not with avocadoes, though this writer sees nothing to scoff at there. Several popular dishes involved serving it slathered with buttered oysters or oysters and cream sauce, and of course, there is the once-famous Welsh Rarebit (also known as Welsh Rabbit) first published in Hannah Glassie’s 1747 The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy. Welsh Rarebit was a nourishing and satisfying dish to enjoy in cold early spring when the only protein remaining in a family’s winter larder was cheese. It enjoyed renewed popularity in the mini-colonial revival of the 1970s, and it deserves to be revived again today when so many of us are rediscovering the comforts of making home baked bread and other indoor entertainments.

Here’s a recipe from The Joy of Cooking. It so happens that Welsh Rarebit goes great with sliced fresh pears. Welsh Rarebit

1 T butter

1/3 C milk

1/2 C ale

8 oz Cheshire or Cheddar cheese, grated or diced

1 t Worcestershire sauce

¼ teaspoon dried mustard pinch cayenne

1 egg yolk

4 slices whole-grain bread

chopped parsley

A handful of toasted almonds

Melt the butter over very low heat in a heavy saucepan. Add the cheese and stir until the cheese melts. Add the cream in the milk and whisk to remove any lumps. Simmer until thickened slightly, about 5 minutes. Stir in the ale and crumble the cheese into the pan; whisk until melted.

Add Worcestershire sauce, mustard and cayenne. Place the egg yolk in a small bowl and whisk until smooth. Add a generous spoonful of the warm cheese mixture to the egg and whisk quickly to combine. Pour the egg yolk mixture into the pan and stir; cook until heated through but not boiling. To serve, toast the bread and place a slice on each plate. Ladle cheese sauce over bread slices and garnish with chopped parsley and toasted almonds. Yield: 4 servings.

Pear-adise at Shirley Place

Pear-adise at Shirley Place

By Eileen Woodfood

The pears in the orchard at Shirley-Place are now beginning to mature. They hang in heavy clusters on the trees along Rockford Street, teasing us–too obvious to ignore, but not yet ready to pick. We wait and watch, anticipating the right moment when we can start to pick them.

We have five varieties of summer pears in our orchard: Seckel, Tyson, Bartlett, Dana’s Hovey, and Clapp’s Favorite. The Tyson, Seckel and Bartlett varieties were cultivated during the 18th century either in Pennsylvania or England, while Dana’s Hovey and Clapp’s Favorite are native to Roxbury during the time that Madame Eustis lived at Shirley-Place.

When our executive director, Suzy Buchanan, asked that I write this article for our newsletter, I enthusiastically took on the assignment. I am just beginning to understand the grounds and plantings of Shirley-Place. Writing these articles helps me deepen my knowledge and expand my understanding so that, as a Governor, I can help the Association make the most informed decisions about how to manage and preserve this exceptional resource.

However, researching our pears was much more difficult than I anticipated. In fact, it was downright maddening. There is a multitude of European pear varieties – in fact, about 3,000. Yet, trying to find any information beyond the superficial on the internet was nearly impossible. While there was some general information about two of our pears, Seckel and Bartlett, there is virtually nothing about the other three varieties in our orchard.

In addition, while there is a lot of information on the history of European pears on the internet from the times of the ancient Greeks through the 17th century, there was virtually no information about pear cultivation in Massachusetts during the 19th century. Our go-to sources on this topic – the Massachusetts Horticultural Society and the Massachusetts Historical Society – were closed and staff generally unavailable. Without the aid of librarians, who really do save us from fruitless internet searches, I could not go beyond what little is readily accessible.

Well, what about our own archives? Unfortunately, we have very little information about our own pear trees other than a few cursory notes. So, I was left to the internet.

Literally after a month of looking, I found two sources that provided more in-depth information–a hobby website of a guy named Anton and the website of a woman who authored a 2015 book on the history of pears in Europe. So, much of what you read here comes from those two sources.

Seckel

According to one enthusiast, “Seckel stands almost alone in vigor of tree, productiveness, and immunity to blight, and is equaled by no other variety in high quality of fruit.” The legend behind this variety is that, toward the end of the 18th century in Philadelphia, a well-known cattle dealer called “Dutch Jacob” would take off each fall for a shooting excursion south of the city. Upon returning to the city, he brought back pears of an “exceedingly delicious flavor” to give to his neighbors, but he kept where they were grown a secret. Eventually, Dutch was able to buy the land with his beloved pear trees, which occupied a neck of land near the Delaware River. However, it was the next owner, a Mr. Seckel, who saw the commercial value of the fruit, named it – after himself -- and introduced it to the market. The new variety was a sensation. As early as 1819, Dr. Hossack of New York sent Seckel varietals to the London Horticultural Society, where they were later distributed in England… Hmm. Our notes at Shirley-Place say that Seckel came to the US from England in 1794. Is there a forgotten pear in England that is really a Seckel, but not acknowledged as such? Whatever the origin of Seckel, the pear was highly regarded during the first half of the 19th century. Henry A.S. Dearborn, a Roxbury resident, noted Massachusetts politician and one of the founders of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society (MHS), exhibited a cluster of 36 Seckel pears at the MHS in 1831, and, at the first meeting of the American Pomological Society, held in 1848, Seckels were recommended for general cultivation.

Tyson

“Ripens early!” screamed one website when describing Tyson. The website waxed on, “…the fruit is sugar-sweet with a hint of spice.” It’s also a vigorous grower and disease tolerant. According conventional internet wisdom, this pear originated in Jenkintown, Pennsylvania in 1794; however, given the mythology around Seckel, it may have a different cultivation story altogether. The 1921 text Pears of New York called the flavor of Tyson “second only the Seckel and stated the “tree is the most nearly perfect of any pear grown in America.” So, why do we not find the “nearly perfect” Tyson in the grocery store anymore? Why are fruit growers not providing us with near taste perfection? Because, according to one website, it went out of favor because it was not as large or pretty as Bartlett.'

Bartlett

In the world of fruit, this is the George Clooney of pears – well built, good looking and with enduring popularity. Even its description matches that of Mr. Clooney: “The flesh is juicy with a sugary, musky flavor…” I’m surprised that we don’t see Mr. Clooney doing advertisements for Bartlett pears. Originating in Berkshire, England in the 1700s as a chance seedling, it is now the world’s most planted variety. (And, why wouldn’t it be with this description?) It is still known by its proper name—Williams’ Bon Chretien—Williams in Europe. So, how did it become known as Bartlett? It’s a similar story to that of Seckel. Enoch Bartlett was a merchant-cum-farmer who bought a farm in Dorchester that had belonged to one Thomas Brewer. Popular accounts state that the farm included a pear orchard that produced excellent pears. Bartlett “thought” that the pears had had grown from seedlings and brought them to market under his own name. However, in 1828 a shipment of pear trees arrived from England – one of the varieties being the Williams pear, and by that time it was “too late” to change back the name of the pear in the US. My middle school teacher “fib radar” lights up big time when I hear this story that it was “too late.” I am skeptical that Mr. Bartlett wanted to take his name away from a fruit that was quickly growing popularity and pushing out the previous stars such as Seckel and Tyson. Who would?

Clapp’s Favorite

According to pear lore, Clapp’s Favorite was raised by Thaddeus Clapp, Dorchester, Massachusetts, but the date of its origin is uncertain. It was favorably mentioned as a promising new fruit at the meeting of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society in 1860. The American Pomological Society first listed Clapp Favorite in its fruit-catalog in 1867. Those of you who live in Dorchester or who have commuted through Edward Everett Square are familiar with this fruit through the 12-foot sculpture of Clapp’s Favorite that stands in the middle of the square. The City of Boston redesigned the square in 2007 with the bronze pear as the centerpiece. It was created by Somerville artist Laura Baring-Gould, who worked on it for five years. The length of time to create her artwork was probably not dissimilar to the time it took to cultivate a prized new fruit variety. To see an image of the pear, click here.

Dana’s Hovey

According to our notes in the files, this pear was developed from the European Winter Seckel pear by Francis Dana of Roxbury in 1854 and named Dana’s Hovey in honor of C.M. Hovey.

Evidently, this is quite the pear when ripe. The fruit is described by one enthusiastic writer as “a delicious little dessert pear, so juicy, sweet, and rich that it is a veritable sweetmeat.”