The Erskine Family in the Shirley Place Tenements, Pt. 1

This article was featured in the Summer 2025 Shirley-Eustis House Newsletter

From 1874 until 1913, the Mansion at Shirley Place was subdivided into apartments and rented out. At any given time, there were approximately seven families living in extremely close quarters with one another. These people held a wide range of jobs: a minister, a barber, watchmaker, teamster, painters, nurse, insurance agent, tailors, cooks, and more. Almost all immigrants to the United States, almost all working class, and many just a single paycheck away from abject poverty.

The residents of Shirley Place were representative of the intense changes Roxbury experienced in the nineteenth century. In less than a century, Roxbury went from a pastoral, well-groomed English landscape to a haven for the working class and for the factories that employed them.

One family in particular stands out among the tenement-era residents at 33 Shirley Street. The Erskines lived here for fourteen years, at some points with three generations inhabiting the same space at one time. It is unclear how many apartments the family rented inside Shirley Place, but it seems to have just been one, as only one of the Erskines was listed as “Head of Household” in each year except for 1890. The family grew and changed over time, but at their peak, there were two older adults, four young adults, and two or more small children in the same apartment. If you have been to Shirley Place, imagine six adults and two young children living in a space the size of the Lafayette bedroom – 400 square feet or even smaller.

The “Erskine” name arrived in Massachusetts at Plimoth in the seventeenth century, while the matrilineal line, Curley, had immigrated to Boston in the mid-nineteenth century from Ireland. This mixture of old Pilgrim heritage and new Irish immigration in the Erskine family is an interesting one. Despite nearly 200 years in North America, the Erskines could not claw their way out of poverty by the Victorian era. Records show that they were still moving frequently, their children were still leaving school to begin working at young ages, and they still suffered from the wear and tear of hard labor and factory pollution on the body. The stereotype of Boston in the late 19th century was that Irish immigrants often suffered a cruel life in pursuit of survival – but evidently, so did families who had been among the first European immigrants to Massachusetts.

In 1891, John Erskine, Sr., the family patriarch, died. His wife Margaret followed not long after, and their son William became the head of household in the apartment. William’s sister Elizabeth also moved back into 33 Shirley Street by 1891 with her three daughters, having lost her husband Charles to influenza around the same time she lost her father. In 1892, then, there were a total of five adults, four children, and one newborn infant in the Erskine apartment at 33 Shirley.

While Elizabeth Erskine Stevens’ children accompanied her back to Shirley Street in 1891, her brother Aaron’s children did not stay with their parents: they were all adopted by other families or living elsewhere by 1900. Aaron and his wife Annie had four children, with three surviving until the 1900 census. Each appeared in a different household in that year, but all still acknowledged their Erskine name. Mary, their eldest child, was a boarder in Dover, Massachusetts in 1900. By 1912, she had married and moved to Northampton. John, their eldest son, died of spinal meningitis in 1906. He was working as a mill hand in Dedham. Joseph, the youngest Erskine, was adopted by a farming family in Dedham. Unusually, the adoptive family listed him as “adopted son,” not just “boarder,” on their census record. At the time, Joseph was just 8 years old.

At the start of my research, it was unclear to me why the Erskine children were farmed out in this way. One hint is in Joseph’s birth record: his name appears in the middle of a batch of children born at or taken to the Temporary Home for Women and Children in Boston’s West End. Only his mother, Annie, is listed as a parent on the record, and no home address is given for Annie or Joseph. At first, I wondered whether Annie was living at the shelter for one reason or another when she gave birth to Joseph. Perhaps she wanted him to have a better life than the one the adult Erskines were experiencing in 1892: packed into tenement housing, suffering from diseases, all forced to work to cobble together an income.

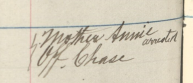

However, I learned something different when following the paper trail in the Temporary Home for Women and Children’s records. Their intake rolls, housed today at the Boston Archives, show that Annie was arrested when Joseph was four months old. Joseph, incorrectly listed as “John” in the paperwork, was taken in at the Temporary Home, and evidently adopted not too long after by his future family in Dedham. It is unclear for what Annie was arrested, and it is unclear where Joseph’s father Aaron was at this time.

When Joseph was adopted, child neglect and cruelty was an issue of paramount importance in Boston. Not just among reformers – in the minds of the public, as well. In her work Heroes of Their Own Lives: The Politics and History of Family Violence, Linda Gordon reports that by 1890, 61% of child cruelty and neglect cases were reported to the Boston authorities by family members of the neglected child. While it is unclear exactly why Annie was arrested and Joseph seized by the Temporary Home, it certainly was a pattern for Annie and Aaron Erskine to lose custody of their children for some reason. And early in each child's life, at that.

Tragedy continued to befall the Erskines. Among the family there was a high mortality rate, even for the time, among children and young adults. Of the eight Erskine grandchildren born between 1874 and 1892, just three lived past the age of twenty. Even among the Erskine children born to John, Sr. and Margaret, disease took its toll. Tuberculosis especially ravaged the Erskine family, as it did most families in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In part two of this story, we’ll examine the impact disease had on the Erskines and other poor families in Boston, especially those living in squalid conditions like the tenements at Shirley Place.